The year is 1947; the place, Brooklyn. The blonde glides through English words in her characteristic Slavic lilt, saying dat for that and skeert for skirt. She pushes vowels out through her nose, and smiles self-consciously when a word escapes her.

If you didn’t know any better, you’d swear it was some young Polish actress cast for the sake of authenticity in the American film. But it’s not. It’s just a girl from New Jersey, Meryl Streep.

Since winning an Oscar for “Sophie’s Choice,” Meryl has set the standard for acting in accent. She’s given us Danish in “Out of Africa,” Australian in “A Cry in the Dark,” Irish in “Dancing at Lughnasa,” and even Julia Child’s singular warble in “Julie and Julia,” to name a few. On Sunday, she’s up for yet another Academy Award for the role of Margaret Thatcher in “The Iron Lady,” which, of course, she delivered in impeccable British parlance.

Performing in a true-to-life foreign dialect is hard. Plenty of actors attempt it. And plenty of them — even the good ones — flop. So what makes Meryl so freakin’ good at it?

Like many things, there’s a hefty dollop of talent involved. But it’s important to distinguish between talent for languages and talent for accents. Think back to high school Spanish class: There was the kid who mastered vocabulary and verb tenses, but his accent would make Neruda groan in his grave. Then there was the girl who couldn’t tell the difference between a pronoun and a participle, but rolled her r’s like a pro.

For actors learning to speak their native tongue with an accent, it’s all about “verbal calisthenics,” not actual language or grammar, says Doug Honorof, a phonetics researcher at the Yale University-affiliated Haskins Laboratories who is also a dialect coach for actors. In other words, it’s a physical process, not a mental one. Honorof compares it to learning a new style of dance: Say you grew up doing the waltz, and all of a sudden you’re trying to salsa.

“You’re still using the same parts of your body, but with a different style and rhythm,” he says. “In the beginning you may trip over your partner’s feet a little bit, but after some practice, you start to get it.”

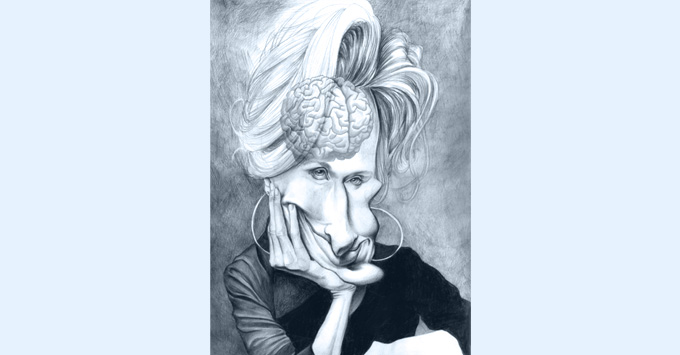

For accents, the relevant parts of the body are the lips, tongue, jaw and vocal chords. Our brains start forming connections with these structures at a very young age, when we first begin to hear and imitate the sounds of whatever language community we find ourselves in. Adopting a different accent as an adult requires, literally, a rewiring of those connections — which feels very odd.

“At some point in the course of developing your voice as an individual, you’ve made a lot of choices about how you’re going to use your lips and tongue,” Honorof says. “To shift that feels very strange, very foreign.”

And yet, Meryl makes it look easy. Could it be that her brain is different than the average person’s?

Perhaps. Neuroscientists have found that the brains of phoneticians, people who study speech sounds for a living, are different from those of people in other professions. It seems the phoneticians have a bit of extra tissue in the auditory cortex — the strip of brain that sits right above the ear and processes incoming sounds. The size of the extra bit didn’t depend on how much training the phoneticians had had, so the researchers believe it was there even before they formally developed their expertise. (In fact, scientists believe that part of the auditory cortex develops in utero, right before birth.) If we assume that actors with a knack for accents are similar to phoneticians, Meryl probably has her Mom and her neuroanatomy to thank, at least in part.

But don’t underestimate the importance of personality. Scientists have also found that people who are more empathetic and extroverted tend to be better at accents. Surprised? You shouldn’t be — after all, children, the undisputed maestros of soaking up languages, are also generally outgoing and not easily embarrassed. Perhaps a key to pulling off accents is warding off those pesky inhibitions that creep in with adulthood.

Honorof says in his experience as a dialect coach, this rule definitely holds up.

“It has something to do with fearlessness,” he explains. An actor’s success with an accent, he says, depends a lot on whether they’re able to convince themselves that they really are the character — that they have “permission” to get on set and be someone else. “If they’re able to psych themselves into it by saying, ‘I am this person, how could I not speak like this?’ that courage makes a huge difference.”

Indeed, in a panel discussion after a screening of “The Iron Lady”, Meryl herself said, “To capture how someone speaks is to capture them.” But while others pile praise on her chameleon voice and struggle to emulate it, she has also referred to accents as “the easiest thing I do, in my brain.”

Go figure. Girl has a gift.